Meet Maya*

- 45 years old

- No medical conditions

- Trusts her OB/GYN and is aware of the benefits of regular cervical cancer screening

- Has cervical cancer screening test every 5 years

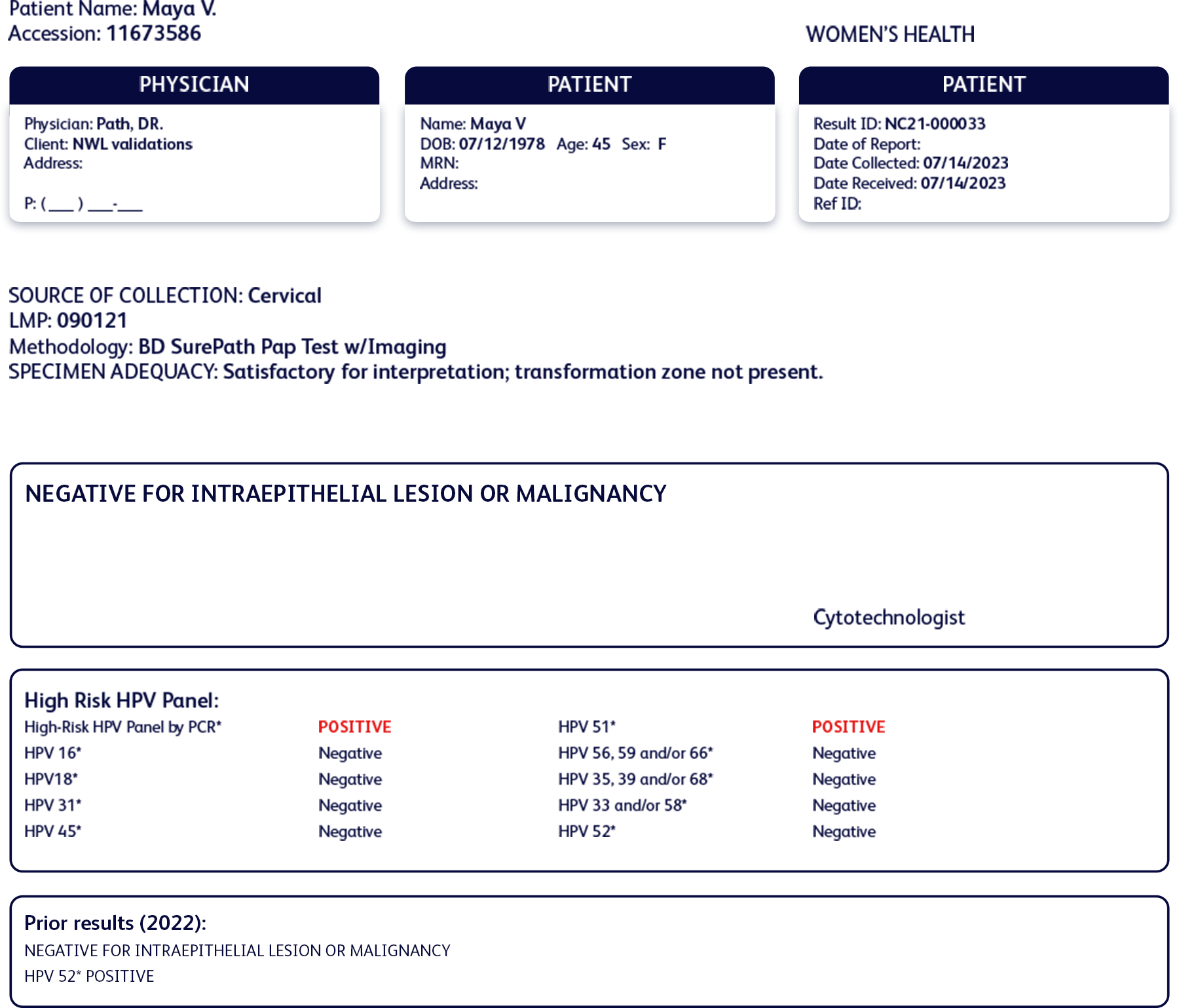

Maya had a positive test result with HPV 52 one year ago and has come back for a follow-up HPV test as instructed by her OB/GYN.

Cervical cancer screening history

Past test results:

- Normal cytology

- Positive for HPV 52

- Negative for all other high-risk HPV types

Current results:

- Normal cytology

- Positive for HPV 51

- Negative for HPV 52 and all other high-risk HPV types

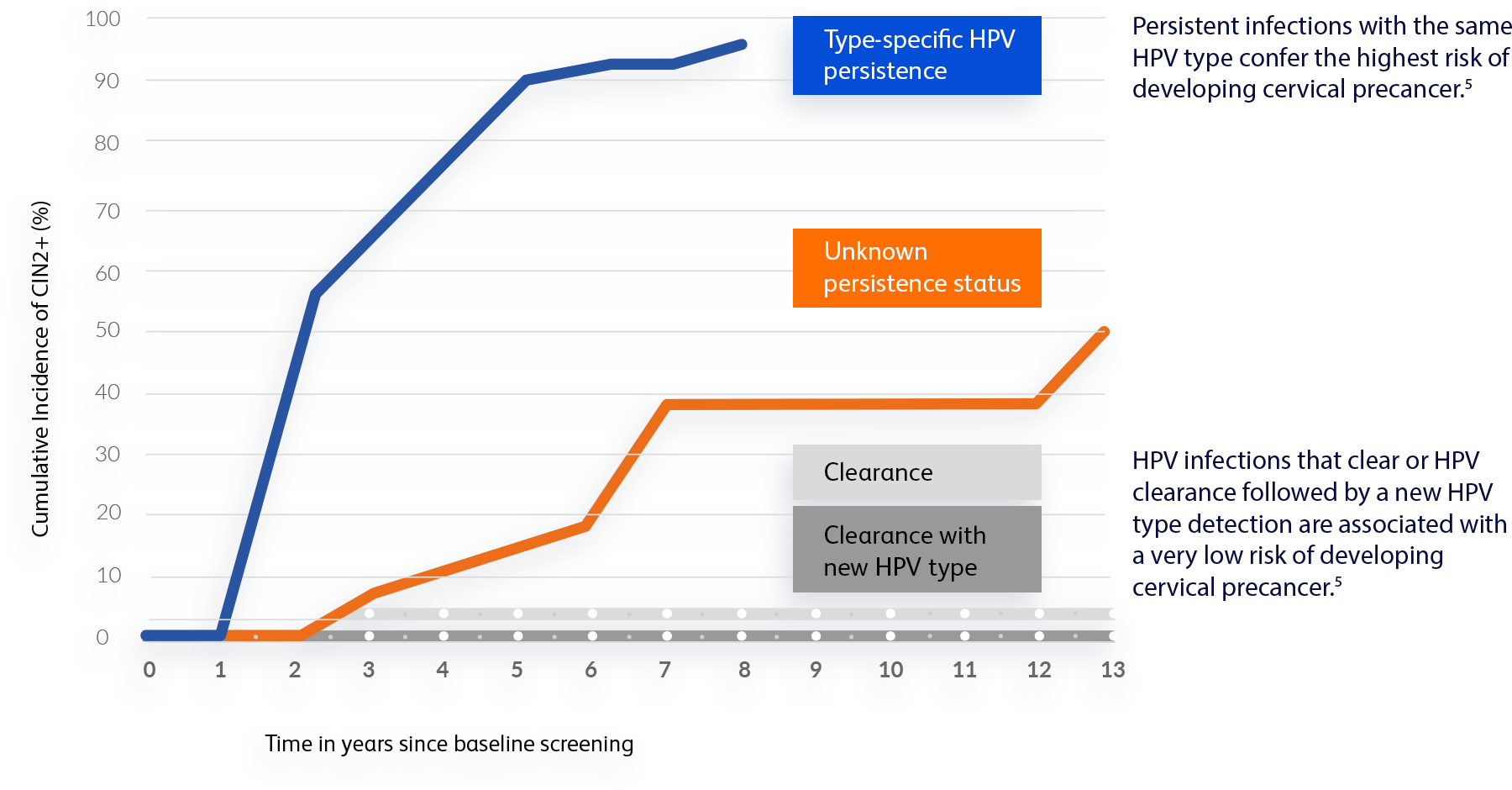

1-year after her initial positive HPV test, she cleared the infection with HPV 52 and tested positive for a different type, HPV 51.

“At first, having a positive result with a different HPV type didn’t make sense to me. Then, my OB/GYN explained that HPV can sometimes be undetectable for years before showing on a test. I’m now reassured because it actually means my risk is lower than if I had the same HPV type as last year.”